The significance of the object of devotion, the Gohonzon, in the practice of Nichiren Buddhism, lies not in the literal meaning of the characters but in the fact that it embodies the life of the original Buddha, or the law of Nam-myoho-renge-kyo. No extra benefit accrues to those who can read the Gohonzon, and knowing what is written on the Gohonzon does not mean that one understands the Gohonzon itself. Some of the characters on the Gohonzon are historical persons, mythical figures or Buddhist gods. Nichiren used them to represent the actual functions of the universe and of our own lives. All these functions are clustered around Nam-myoho-renge-kyo; therefore, the Gohonzon is the embodiment of the life of Buddhahood within us.

At one time, the second president of the Soka Gakkai, Josei Toda, explained the purpose of embracing the Gohonzon as follows:

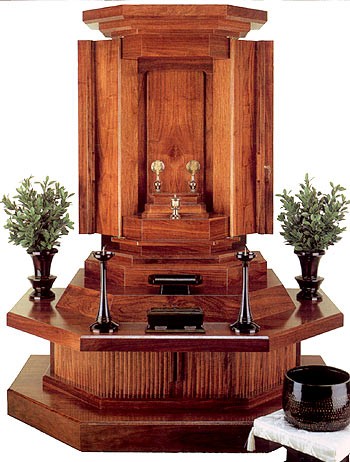

The Gohonzon, in a sense, can be compared to a map pointing to the location of the supreme treasure of life and the universe-the Mystic Law of Nam-myoho-renge-kyo (Click here to see a diagram of the Gohonzon). This treasure map tells us that the treasure is found within our lives. To those who can understand the map, it is not just a piece of paper but an invaluable object equal in value to the “treasure,” that is, life’s supreme condition and potential itself. To those who fail to grasp its message, however, the map’s worth will be reduced to that of a mere scroll. As Nichiren says:

How then can we correctly understand this map and locate the treasure it leads to? The Daishonin encourages us, “When you chant the myoho and recite renge, you must summon up deep faith that Myoho-renge-kyo is your life itself” (WND-1, 3). Nichiren Daishonin teaches us, in other words, that one’s life is the greatest treasure. Hence he also writes: “Never seek this Gohonzon outside yourself. The Gohonzon exists only within the mortal flesh of us ordinary people who embrace the Lotus Sutra and chant Nam-myoho-renge-kyo” (WND-1, 832). This realization is what Buddhism calls the condition of enlightenment.

To convey his message, Nichiren used the theory of a life-moment possessing 3,000 realms especially the mutual possession of the ten worlds as a basis for the Gohonzon’s graphic image. The Gohonzon itself is the world of Buddhahood in which all the other worlds are represented. This is the depiction of mutual possession.

Down the center of the Gohonzon is written “Nam-myoho-renge-kyo-Nichiren” (Nos. 1 and 2 respectively on the chart). This illustrates the oneness of the person and the law, or that Nichiren’s life itself embodies the Mystic Law, as he writes, “The soul of Nichiren is nothing other than Nam-myoho-renge-kyo” (MW-1, 120). It also indicates that our lives are fundamentally one and the same with the law of Nam-myoho-renge-kyo, as Nichiren demonstrated through his life. Put another way, the inscription of “Nam-myoho-renge-kyo -Nichiren” tells us that we have the identical qualities of the original Buddha’s life. To the degree we strive for kosen-rufu and pray with the same desire as Nichiren, we will manifest the same courage, hope and wisdom. This is what he meant when he wrote:

To the left and right of “Nam-myoho-renge-kyo-Nichiren” are various figures that represent the ten worlds in the life of the Buddha. Nichiren included them on the Gohonzon to indicate that even the Buddha’s life inherently contains the lower nine worlds.

By writing “Nam-myoho-renge-kyo-Nichiren” prominently down the center with the other, smaller characters around it, Nichiren graphically indicated that the figures representing the lower nine worlds are illuminated by the Mystic Law, as he writes: “Illuminated by the light of the five characters of the Mystic Law, they display the dignified attributes that they inherently possess. This is the object of devotion” (WND-1, 832). In other words, these figures signify the nine worlds contained within Buddhahood.

A Clear Mirror of Life

In contrast to worshiping the Buddha or Law as externals, the Great Teacher T’ien-t’ai of China, basing his teaching on the Lotus Sutra, set forth a meditative discipline for attaining enlightenment. He called this “observing the mind.” T’ien-t’ai’s philosophy recognized the potential for Buddhahood in all people. But his practice was too difficult to carry out amid the challenges of daily life. Only those of superior ability, living in secluded circumstances, had a chance of attaining enlightenment.

Nichiren Daishonin established a teaching and practice to directly awaken the innate enlightened nature in any human being— the practice of chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo (see An Introduction to Buddhism, pp. 11–15). Enlightenment, more than just a state of mind, encompasses the totality of our mental, spiritual and physical being, as well as our behavior. Introspection alone, as in T’ien-t’ai’s teachings, is inadequate for attaining enlightenment.

Nichiren inscribed the Gohonzon to serve as a mirror to reflect our innate enlightened nature and cause it to permeate every aspect of our lives. SGI President Ikeda states: “Mirrors reflect our outward form. The mirror of Buddhism, however, reveals the intangible aspect of our lives. Mirrors, which function by virtue of the laws of light and reflection, are a product of human wisdom.

On the other hand, the Gohonzon, based on the law of the universe and life itself, is the culmination of the Buddha’s wisdom and makes it possible for us to attain Buddhahood by providing us with a means of perceiving the true aspect of our life” (My Dear Friends in America, third edition, p. 94).

And just as we would not expect a mirror to apply our makeup, shave our beards or fix our hair, when we chant to the Gohonzon, we do not expect the scroll in our altars to fulfill our wishes. Rather, with faith in the power of the Mystic Law that the Gohonzon embodies, we chant to reveal the power of our own enlightened wisdom and vow to put it to use for the good of ourselves and others.

Nichiren, emphasizing the nature of the Gohonzon’s power, writes: “Never seek this Gohonzon outside yourself. The Gohonzon exists only within the mortal flesh of us ordinary people who embrace the Lotus Sutra and chant Nam-myoho-renge-kyo” (“The Real Aspect of the Gohonzon,” WND-1, 832).

An Expression of Nichiren’s Winning State of Life

From childhood, Nichiren Daishonin ignited within himself a powerful determination to rid the world of misery and lead people to lasting happiness. With this vow, he thoroughly studied the sutras and identified chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo as the practice that embodies the essence of Shakyamuni’s teachings. In the course of propagating this practice, Nichiren overcame numerous harsh persecutions, including attempts on his life.

After the failed attempt to execute him at Tatsunokuchi in 1271, Nichiren began to inscribe the Gohonzon and bestow it upon staunch believers. Regarding this, he said: “From that time, I felt pity for my followers because I had not yet revealed this true teaching to any of them. With this in mind, I secretly conveyed my teaching to my disciples from the province of Sado” (“Letter to Misawa,” WND-1, 896).

Nichiren emerged victorious over the most powerful religious and secular oppression, and resolved to leave a physical expression of his winning state of life so all future disciples could bring forth that same life condition.

Writing to his samurai disciple Shijo Kingo, he stated: “In inscribing this Gohonzon for [your daughter’s] protection, Nichiren was like the lion king. This is what the sutra means by ‘the power [of the Buddhas] that has the lion’s ferocity.’ Believe in this mandala with all your heart. Nam-myoho-renge-kyo is like the roar of a lion. What sickness can therefore be an obstacle?” (“Reply to Kyo’o,” WND-1, 412).

The Treasure Tower

“The Emergence of the Treasure Tower,” the 11th chapter of the Lotus Sutra, describes a gigantic tower adorned with precious treasures emerging from beneath the earth and hovering in the air. Nichiren explains that this tower is a metaphor for the magnitude of the human potential—the grandeur of the Buddha nature within all people (see “On the Treasure Tower,” WND-1, 299).

Next, the sutra describes the Ceremony in the Air—a vast assembly of Buddhas, bodhisattvas and beings of every description, gathering from all corners of the cosmos. The Buddha employs special powers to raise the entire assembly into the air before the treasure tower. He then begins preaching his teaching.

Nichiren chose to depict on the Gohonzon, in written form, key elements of this Ceremony in the Air. Nam-myoho-renge-kyo, representing the treasure tower, is inscribed down the center of the Gohonzon. Rather than a painted or sculpted image, which could not sufficiently capture the totality of a Buddha, Nichiren employed written characters on the Gohonzon to communicate the state of oneness with the Mystic Law that he realized in his own life. According to President Ikeda: “Such [a statue or image] could never fully express Nam-myoho-renge-kyo, the fundamental Law that includes all causes (practices) and effects (virtues). The invisible attribute of the heart or mind, however, can be expressed in words” (June 2003 Living Buddhism, p. 34).

President Ikeda also emphasizes: “Through our daily practice of reciting the sutra and chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo, we can join the eternal Ceremony in the Air here and now. We can cause the treasure tower to shine within us and to shine within our daily activities and lives. That is the wonder of the Gohonzon. A magnificent cosmos of life opens to us, and reality becomes a world of value creation” (June 2003 Living Buddhism, p. 32).

The Gohonzon Exists in Faith

While most can agree that everyone possesses a wonderful potential within, truly believing this about all people and living based on this belief is not easy. Nichiren Daishonin inscribed the Gohonzon so that anyone can believe in and activate his or her Buddha nature. Just having the Gohonzon, however, will not ensure this. Both faith and practice are essential to unlocking our powerful Buddha nature. Nichiren says: “This Gohonzon also is found only in the two characters for faith. This is what the sutra means when it states that one can ‘gain entrance through faith alone’ . . . What is most important is that, by chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo alone, you can attain Buddhahood. It will no doubt depend on the strength of your faith. To have faith is the basis of Buddhism” (“The Real Aspect of the Gohonzon,” WND-1, 832).

The Banner of Propagation

Nichiren Daishonin also says, “I was the first to reveal as the banner of propagation of the Lotus Sutra this great mandala” (“The Real Aspect of the Gohonzon,” WND-1, 831).

Today, the SGI, through the leadership of its three founding presidents—Tsunesaburo Makiguchi, Josei Toda and Daisaku Ikeda—has embraced the Gohonzon as Nichiren truly intended—as a “banner of propagation” of the Buddhist teaching that can lead humankind to peace and happiness. For that reason, members who chant Nam-myoho-renge-kyo to the Gohonzon and exert themselves in SGI activities to spread the Law in the spirit of the three presidents achieve remarkable growth, benefit and victory in their lives. (An Introduction to Buddhism, pp. 31–35)

Faith Equals Daily Life

The purpose of religion should be to enable people to lead happy, fulfilling lives. Buddhism exists for this very reason. While many tend to view Buddhism as a reclusive practice of contemplation aimed at freeing the mind from the concerns of this world, this is by no means its original intent. Seeking to deny or escape the realities of life or society does not accord with the genuine spirit of Buddhism. Enlightenment, which Buddhism aims for, is not a transcendent or passive state, confined to the mind alone. It is an all-encompassing condition that includes an enduring sense of fulfillment and joy, and permeates every aspect of our lives, enabling us to live in the most valuable and contributive way. This idea is expressed in the SGI through the principle that “faith equals daily life.”

Nichiren Daishonin stressed this idea from many angles in his writings, often quoting the Great Teacher T’ien-t’ai’s statement that “no worldly affairs of life or work are ever contrary to the true reality” (“Reply to a Believer,” The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, vol. 1, p. 905). When, through our Buddhist practice, our inner condition becomes strong and healthy—when we bring forth the “true reality” of our innate Buddha nature—we can act with energy and wisdom to excel at school or work and contribute to the wellbeing of our families and communities.

Regarding the principle that faith equals daily life, “daily life” points to the outward expressions of our inner life. And “faith,” our Buddhist practice, strengthens the power within us to transform our inner lives at the deepest level. When we apply our practice to the issues and problems we encounter in daily life, those challenges become stimuli—causes or conditions—that enable us to bring forth and manifest Buddhahood. Our daily lives become the stage upon which we carry out a drama of deep internal life reformation.

Nichiren writes: “When the skies are clear, the ground is illuminated. Similarly, when one knows the Lotus Sutra, one understands the meaning of all worldly affairs” (“The Object of Devotion for Observing the Mind,” WND-1, 376). For us, “knowing the Lotus Sutra” means chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo courageously to the Gohonzon and participating in SGI activities for our own and others’ happiness. This causes our Buddha nature to surge forth, infusing us with rich life force and wisdom. We in effect come to “understand the meaning of all worldly affairs.” The teaching and practice of Buddhism enable us in this way to win in daily life.

A scholar recently noted that one reason the SGI has attracted such a diverse group of people over the years is that it emphasizes and encourages people to apply Buddhist practice to winning in their lives. This accords with Nichiren’s emphasis on actual results as the most reliable gauge of the validity of a Buddhist teaching. As he says, “Nothing is more certain than actual proof” (“The Teaching, Practice, and Proof,” WND-1, 478).

At monthly SGI discussion meetings, members share experiences that result from faith and practice, and joyfully refresh their determination to advance and grow. The Soka Gakkai’s founding president, Tsunesaburo Makiguchi, established the discussion-meeting format before World War II. He described them as venues to “prove experimentally the life of major good” (The Wisdom of the Lotus Sutra, vol. 2, p. 118). Hearing and sharing experiences in faith give us insight into how Buddhist practice enriches people’s lives and inspire us to strengthen our resolve. Discussion meetings are forums for confirming the purpose of Buddhism, which is to enable every person to win in life and become happy.

We should also understand that chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo produces the most meaningful rewards when accompanied by action or effort.

Any religion promising results without effort would be akin to magic. But even if we could get what we wanted through magic, we would not grow in character, develop strength or become happy in the process. Buddhist practice complements and strengthens the effects of any effort. A student may chant to ace a test, but the surest path to passing is to match such prayers with serious effort in study. The same applies to all matters of daily living.

The power of chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo to the Gohonzon is unlimited. It infuses us with the energy we need to keep striving and with the wisdom to take the best, most effective action. When we act wielding this energy and wisdom, we will undoubtedly see our prayers realized.

President Ikeda says: “The Gohonzon is the ultimate crystallization of human wisdom and the Buddha wisdom. That’s why the power of the Buddha and the Law emerge in exact accord with the power of your faith and practice. If the power of your faith and practice equal a force of one hundred, then they will bring forth the power of the Buddha and the Law to the degree of one hundred. And if it is a force of ten thousand, then it will elicit that degree of corresponding power” (Discussions on Youth, second edition, p. 299).

Nichiren Daishonin instructed one of his disciples—a samurai named Shijo Kingo who lived in the military capital, Kamakura—as follows: “Live so that all the people of Kamakura will say in your praise that Nakatsukasa Saburo Saemon-no-jo [Shijo Kingo] is diligent in the service of his lord, in the service of Buddhism, and in his concern for other people” (“The Three Kinds of Treasure,” WND-1, 851). At the time, Kingo had been subject to jealousy among his warrior colleagues, some of whom had spread rumors and made false reports about him to his feudal lord. But taking Nichiren’s encouragement to heart, Kingo strove to act with sincerity and integrity, and thereby strengthened his ability to assist his lord—to do his job, in today’s terms.

Nichiren also encouraged him that the entire significance or purpose of Buddhism lies in the Buddha’s “behavior as a human being” (WND-1, 852) to fundamentally respect all people. This suggests that as Buddhists our sincere and thoughtful behavior toward others is of paramount importance.

Eventually Kingo regained his lord’s trust and received additional lands, showing proof of the power of applying Nichiren’s teaching to life’s realities.

When President Ikeda visited the United States in 1990, he said to SGI-USA members: “I also sincerely hope that, treasuring your lives and doing your best at your jobs, each of you without exception will lead a victorious life. It is for this reason that we carry out our practice of faith” (My Dear Friends in America, third edition, p. 22).

We can view our immediate environment and responsibilities—at work, in our families and in our communities—as training grounds in faith and in life. In this way, we can use every difficulty as an opportunity to further activate our inherent Buddha nature through chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo, and win in the affairs of society. Then we can grasp the real joy of applying the principle that faith equals daily life.